To many of the cultured, the name Walt Disney, signifies a bastardization of literary classics they have grown up with or appreciated--a completely Americanized reworking of European fairy tales or fables from other countries. Disney could usually be counted on to display an obsessive desire to conquer the aphoristic core of the work and claim the ideas as his own.

It is probably bourgeois to most erudite thinkers to accept that forward American as an intellect or aspiring scholar. Seldom is Disney thought of as a legitimate introduction to literature or an explorer of unfamiliar treasures by classic authors.

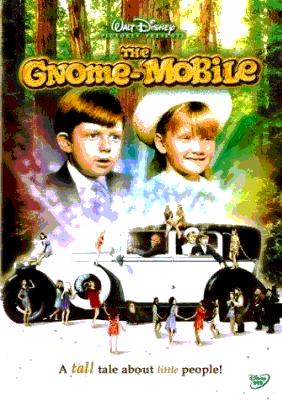

Upton Sinclair's book, The Gnomemobile, or, a Gnice Gnew Gnarrative with Gnonsense, but Gnothing Gnaughty,' is definitely the American author's least known and discussed book. At the time this article was written, the book was out of print and not available in libraries in this area. It was equally hard to locate elsewhere. That Walt Disney was aware, or made aware, says something of his literary ingenuity.

The Sinclair book concerns the destruction of our nation's redwood forest, the natural habitat of those mythical creatures called gnomes. The book is dedicated by Sinclair to, "all who love and protect our forest". Its story approaches the problem of depleting environmental resources which was at the height of controversy many years later in the 1980's. Even the President, during that time, was quoted as saying, "if you've seen one redwood, you've seen them all". The 1980's were not noted for social conscience.

The Disney studios did not have to exhaust themselves making their domestic audience feel familiar and comfortable with the story, something they felt inclined to do with European or foreign material. Though the Disney film only utilizes California and Washington, there is a wealth of Americana vividly described by Sinclair. In the book, the search for gnomes treks across a good part of the United States, including California, Washington, Utah, and finally ends in Pennsylvania.

Not having to deal with the process of Americanization, this left the studio plenty of time to do what they do best, literary impudence. The Disney writers never simply adapted literature to film, they 'Disneyfied' it, a term used by Disney aficionados which means distorting the original work to such an extent that it is almost unrecognizable as anything other than Disney. The British writer P.L. Travers was displeased with the Disney interpretation of Mary Poppins. It can easily be imagined that the similar treatment the film studio gave the writings of others, such as Barrie or Carroll, would have been disturbing to those authors as well. Being an American himself, it's hard to think of what Sinclair would have felt about the Disney approach. Considering the film was released around the time of his death in 1968, Sinclair may or may not have seen the film.

In the film, the protagonists share only a passing resemblance to those in the book. They differ in name, age and personality, often to suit the Disney formula and make them more suited to mass taste. Oddly enough, there is still some of the original essence left.

In Sinclair's story, the two principal characters are Elizabeth, a nine-year-old child, and Rodney, her twenty-three-year-old uncle. In the Disney version, the names are the same, but they are both children of nine or ten years, acted by Disney regulars, Matthew Garber and Karen Dotrice.

The capitalist lumber mogul, who busily depletes redwood trees, is named Sinsabow in the book. He is only referred to by the other characters and never takes part in the adventures. In the film he is the main character and his name is changed to D.J. Mulrooney.

Sinclair depicts the Sinsabow character as an indifferent business man concerned more with profit than with humanity or the environment. Disney's Mulrooney is sympathetic instead of money-minded. Mulrooney is an endearing grandfather type,played by American favorite, Water Brennan. Mulrooney sings to his grandchildren and has a deep concern for the plight of the gnomes. This relieved the Disney studio of otherwise politically loaded content. Brennan also plays the part of the grandfather gnome which also helps to make him seem even more cute and appealing.

Sinclair's book is full of whimsical poetry recited throughout the travels. The poetry is eliminated in the film and replaced by a catchy commercial jingle designed to appeal to audiences with less lyrical sensibilities who might find poetry too delicate for their taste.

The most surprising change is the ending. Sinclair's ending has the gnomes finding their lost breed living inside of a rock in Pennsylvania. The newly discovered gnomes live an industrial lifestyle full of factories, high-rise buildings, sports cars, and, yes, even unemployment. The Disney ending has the gnome colony living a rustic lifestyle in the woods outside Oregon. Their life is simple and without modern conveniences. This seems odd, since it would appear to be more in character for Disney to imagine mythical creatures living a capitalist existence.

The Sinclair book is intelligent and understated compared with the Disney film which is shamelessly low-brow and raucous. The film has no shortage of gimmicks, car-crashes, slapstick and even features scantily-clad female gnomes who look like Playboy bunnies from Hugh Hefner's over-sexed imagination. The girls hardly seem suitable in a film designed for children, but Disney constantly displayed a penchant for vulgar sexuality in supposedly wholesome entertainment. Sinclair's female gnomes are more reserved and well-dressed.

Special optical and mechanical effects seem to be a continuous fascination throughout the Disney film. The photography of humans and gnomes together is startling. There is an especially convincing sequence where the younger gnome is chased about a room by an exhibitor who wants to catch the gnome for a circus. The sequence ends with the gnome leaping out of a window only to be reeled back inside by the human using a fishing rod. The film manipulates people and objects effectively by employing this kind of mind-blowing technology. There are even robotic birds, raccoons and other woodland animals. The robotic effect is obvious, but knowing they are robots is not less impressive technically.

The main problem with special visual effects is that they create chaos and inhibit intellectual development. Rather than being sincere or charming, Disney films often make rowdy spectacles of themselves. Disney never seemed to realize that Hollywood films are full of gimmicks, and most of them are quite competent. Gimmicks do not make a story intelligent or thoughtful, they render it sensation-oriented. This kind of emphasis on visuals usually leads to a story lacking insight or plot development. The trend toward relying on special gimmicks became full-blown in Hollywood films of the 1980's and 90's, especially in the films of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Most recent special effects extravaganzas have about as much reserve as bungee jumping.

The looney antics in Disney films may please ill-behaved youngsters who refuse to sit through any kind of cerebral activity or read a book, but may cause headache and irritation for some adults who prefer their little ones to practice more sensible and self-disciplined behavior. It may sound like too much of a requirement, but children are probably capable of more complex thinking than we credit them with.

The Disney version may well have been the only way to have adapted this fine book to film. Things that work well in written word do not always transfer well to cinema. Most theater audiences seem to prefer brisk moving strategy to drawn-out philosophical introspection, at least in commercial entertainment they do. But even though Disney attempts to make mass audiences aware of Sinclair's much neglected book, a noble gesture really, children are more likely to receive a more accurate introduction to Upton Sinclair by reading the book. The book is gentle, whereas the film, like most Hollywood theater, is guided by sensation.

I do not want to give a misleading impression of the Disney film as bad. Children are intrigued by Disney much the same way they might be be by a circus or a christmas tree. Disney understands children very well and caters to them with quality commercial entertainment. Children like things that are outrageous and fun, something Disney and Hollywood do best.

My respects to both Mr. Sinclair and Mr. Disney, for they are both remarkable men in their individual manners.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Maltin, Leonard with Jerry Beck (research associate). The Disney Films (New York: Crown,1984).

Vig, Norman J and Michael E. Kraft (eds). Environmental Policy in the 1990's: Toward a new agenda (Washington, D.C.: Cq Press, 1990).

Links

James Johnston

353 West Barnett Street

Ventura, California 93001

(805) 648 5077

e-mail: johnstonjames@rocketmail.com

web address: http://gnomemobile.angelfire.com

Last Updated: November 19, 2008

Return to top of page.